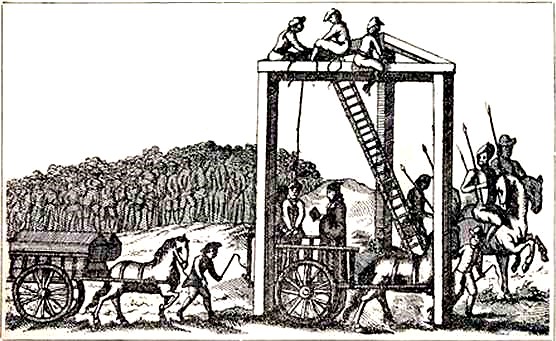

L'arbre de Tyburn' où furent exécutés la plupart des martyrs

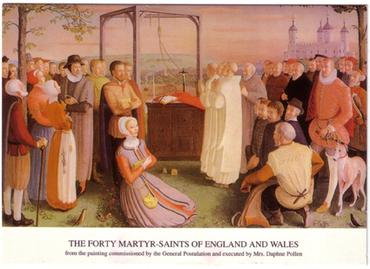

Quarante martyrs d'Angleterre et du Pays de Galles

catholiques martyrisés en Angleterre et au Pays de Galles entre 1535 et 1679

Groupe de quarante martyrs canonisés le 25 octobre 1970 par le pape Paul VI pour représenter les catholiques martyrisés en Angleterre et au Pays de Galles entre 1535 et 1679.

Anglais et gallois, qui entre 1535 et 1679, ont été martyrs de leur fidélité à l'Église catholique

romaine. Ils sont fêtés le jour de leur canonisation commune, parce que l'unité de leur foi les a réunis malgré des dates éloignées... Durant ces années de persécutions, parce qu'ils refusaient l'adhésion au schisme du roi d'Angleterre, chacun à sa manière a souscrit à cette parole de saint John Plessington: "Que Dieu bénisse le roi et sa famille et daigne accorder à sa Majesté un règne prospère en cette vie et une couronne de gloire en l'autre. Que Dieu accorde la paix à ses sujets en leur donnant de vivre dans la vraie foi, dans l'espérance et dans la charité."

Alexandre Bryant,

David Lewis,

Jean Lloyd,

Luc Kirby

Philippe Evans,

Philippe Howard,

Polydore Plasden,

Prêtres missionnaires et autres catholiques ayant été martyrisés en Angleterre à cause de leur religion entre 1577 et 1684.

Extraits de l'homélie de Paul VI:

Les martyrs ont offert à Dieu le sacrifice de leur vie, poussés par le plus haut et le plus grand amour.

L'Église continue à croître et à grandir par l'amour héroïque qui anime les martyrs... Notre siècle a besoin de saints! Il a surtout besoin de l'exemple de ceux qui ont donné le témoignage suprême de leur amour pour le Christ et pour son Église: «Il n'y a pas de plus grand amour que de donner sa vie pour ceux qu'on aime.»

![]()

Paul VI Homélies 28050

25100

La canonisation solennelle des Quarante martyrs de l'Angleterre et du Pays de Galles que nous venons d'accomplir nous offre l'heureuse occasion de vous parler, bien que brièvement, du sens de leur existence et de l'importance que leur vie et leur mort ont eus et continuent d'avoir non seulement pour l'Eglise d'Angleterre et du Pays de Galles, mais aussi pour l'Eglise Universelle et pour tout homme de bonne volonté.

Notre temps a besoin de saints et, d'une manière spéciale, de l'exemple de ceux qui ont donné le suprême témoignage de leur amour pour le Christ et pour l'Eglise : « Personne n'a un amour plus grand que celui qui donne sa vie pour ses amis » (Jn 15,13). Ces paroles du divin Maître, qui se rapportent en premier lieu au sacrifice que Lui-même accomplit sur la croix en s'offrant pour le salut de toute l'humanité valent aussi pour la grande foule choisie des martyrs de tous les temps, depuis les premières persécutions jusqu'à celles de nos jours, peut-être plus cachées mais pas moins cruelles. L'Eglise du Christ est née du sacrifice du Christ sur la croix et elle continue à croître et à se développer en vertu de l'amour héroïque de ses fils les plus authentiques. « Semen est sanguis christianorum » (tertullianus, Apologeticus, 50 ; PL 1, 534). De même que l'effusion du sang du Christ, l'oblation que les martyrs font de leur vie devient, en vertu de leur union avec le sacrifice du Christ, une source de vie et de fécondité spirituelle pour l'Eglise et pour le monde tout entier. « C'est pourquoi, nous rappelle la Constitution Lumen gentium, 42, le martyre dans lequel le disciple est assimilé au Maître acceptant librement la mort pour le salut du monde et dans lequel il devient semblable à Lui dans l'effusion de son sang, est considéré par l'Eglise comme une grâce éminente et la preuve suprême de la charité ».

Beaucoup de choses ont été dites et écrites sur cet être mystérieux qu'est l'homme : sur les ressources de son esprit, capable de pénétrer dans les secrets de l'univers et de soumettre les choses matérielles en les utilisant pour arriver à leurs buts ; sur la grandeur de l'esprit humain qui se manifeste dans les oeuvres admirables de la science et de l'art ; sur sa noblesse et sur sa faiblesse, sur ses triomphes et sur ses misères. Mais ce qui caractérise l'homme, ce qu'il y a de plus intime dans son être et dans sa personnalité, c'est la capacité d'aimer, d'aimer jusqu'au fond, de se donner avec cet amour qui est plus fort que la mort et qui se prolonge dans l'éternité.

Le martyre des chrétiens est l'expression et le signe le plus sublime de cet amour, non seulement parce que le martyr reste fidèle à son amour jusqu'à l'effusion de son propre sang, mais aussi parce que ce sacrifice est accompli pour l'amour le plus haut et le plus noble qui puisse exister, à savoir pour l'amour de Celui qui nous a créés et rachetés, qui nous a aimés comme Lui seul sait aimer, et qui attend de nous une réponse de don total et sans conditions, c'est-à-dire un amour digne de notre Dieu.

Signe d'amour

Dans sa longue et glorieuse histoire, la Grande Bretagne, île des saints, a donné au monde beaucoup d'hommes et de femmes qui ont aimé Dieu de cet amour pur et loyal : c'est pour cela que nous sommes heureux d'avoir pu aujourd'hui compter quarante autres fils de cette noble terre parmi ceux que l'Eglise reconnaît publiquement comme saints, les proposant ainsi à la vénération de ses fidèles, et parce que ces saints représentent par leurs existences un exemple vivant.

A celui, qui, ému et saisi d'admiration, lit les actes de leur martyre, il est clair, nous voudrions dire évident, qu'ils sont les dignes émules des plus grands martyrs des temps passés, en raison de la grande humilité, de l'intrépidité, de la simplicité et de la sérénité avec lesquelles ils ont accepté leur sentence et leur mort et même plus encore avec une joie spirituelle et une charité admirable et radieuse.

C'est justement cette attitude profonde et spirituelle qui groupe et unit ces hommes et ces femmes qui, par ailleurs, étaient très différents entre eux par tout ce qui peut différencier un ensemble nombreux de personnes, à savoir l'âge et le sexe, la culture et l'éducation, l'état de vie et la condition sociale, le caractère et le tempérament, les dispositions naturelles et surnaturelles, les circonstances extérieures de leur existence. Nous avons en effet, parmi les quarante saints martyrs, des prêtres séculiers et réguliers, nous avons des religieuses de divers ordres et de rangs divers, nous avons des laïcs, des hommes de très noble descendance et aussi de condition modeste, nous avons des femmes qui étaient mariées et mères de famille : ce qui les unissait tous, c'est cette attitude intérieure de fidélité inébranlable à l'appel de Dieu qui leur demanda, comme réponse d'amour, le sacrifice même de leur vie.

Et la réponse des martyrs fut unanime : « Je ne peux pas m'empêcher de vous répéter que je meurs pour Dieu et à cause de ma religion — c'est ce que disait saint Philip Evans — et je me sens si heureux que si jamais je pouvais avoir beaucoup d'autres vies, je serais très disposé à les sacrifier toutes pour une cause aussi noble ».

Loyauté et fidélité

Et, comme par ailleurs de nombreux autres, saint Philip Howard, comte d'Arundel, affirmait aussi : « Je regrette de n'avoir qu'une vie à offrir pour cette noble cause ». Et sainte Margaret Clitherow exprimait synthétiquement, avec une simplicité émouvante, le sens de sa vie et de sa mort : « Je meurs pour l'amour de mon Seigneur Jésus ». « Quelle petite chose, en comparaison de la mort bien plus cruelle que le Christ a soufferte pour moi », s'écriait saint Alban Roe.

Comme beaucoup de leurs compatriotes qui moururent dans des circonstances analogues, ces quarante hommes et femmes de l'Angleterre et du Pays de Galles voulaient être et le furent à fond, loyaux, envers leur patrie qu'ils aimaient de tout leur coeur. Ils voulaient être et ils furent en fait de fidèles sujets du pouvoir royal que tous, sans aucune exception, reconnurent jusqu'à leur mort comme légitime en tout ce qui appartenait à l'ordre civil et politique. Mais ce fut là justement le drame de l'existence de ces martyrs, à savoir que leur honnête et sincère loyauté envers l'autorité civile se trouva en désaccord avec la fidélité envers Dieu et qu'ainsi, suivant les préceptes de leur conscience éclairée par la foi catholique, ils surent conserver les vérités révélées, spécialement sur la sainte Eucharistie et sur les prérogatives inaliénables du successeur de Pierre qui, par la volonté de Dieu, est le pasteur universel de l'Eglise du Christ. Placés devant le choix de rester fermes dans leur foi et donc de mourir pour elle ou d'avoir la vie sauve en reniant la foi, sans une minute d'hésitation et avec une force vraiment surnaturelle, ils se rangèrent du côté de Dieu et affrontèrent le martyre avec joie. Mais leur esprit était si grand, si nobles étaient leurs sentiments, si chrétienne était l'inspiration de leur existence que beaucoup d'entre eux moururent en priant pour leur patrie tant aimée, pour le roi et pour la reine et même pour ceux qui avaient été les responsables directs de leur arrestation, de leurs tortures et des circonstances ignominieuses de leur mort atroce.

Les dernières paroles et la dernière prière de saint John Plessington furent précisément celles-ci : « Que Dieu bénisse le roi et sa famille et daigne accorder à Sa Majesté un règne prospère en cette vie et une couronne de gloire en l'autre. Que Dieu accorde la paix à ses sujets en leur donnant de vivre et de mourir dans la vraie foi, dans l'espérance et dans la charité ».

Activité et sacrifice

Voici comment pria saint Alban Roe peu de temps avant d'être pendu : « Pardonnez-moi, ô mon Dieu, mes innombrables offenses comme je pardonne à mes persécuteurs » et, comme lui, saint Thomas Garnet qui, après avoir nommé particulièrement ceux qui l'avaient livré, arrêté et condamné, supplia Dieu en disant : « Puissent-ils tous obtenir le salut et avec moi atteindre le ciel ».

En lisant les actes de leur martyre et en méditant la riche matière qui a été recueillie avec tant de soin sur les circonstances historiques de leurs vies et de leur martyre, nous restons frappés surtout par ce qui brille sans équivoque dans leur existence. Cela, par sa nature même, peut traverser les siècles et par conséquent rester toujours pleinement actuel et, spécialement de nos jours, d'une importance capitale. Nous nous rapportons au fait que ces héros, fils et filles de l'Angleterre et du Pays de Galles, ont pris leur foi vraiment au sérieux : cela veut dire qu'ils l'acceptèrent comme l'unique règle de leur vie et de toute leur conduite, en retirant une grande sérénité et une profonde joie spirituelle. Avec une fraîcheur et une spontanéité non séparées de ce don précieux de l'humour, typiquement particulier à leur peuple, avec un attachement à leur devoir fuyant toute ostentation et avec la pureté typique de ceux qui vivent avec des convictions profondes et bien enracinées, ces saints martyrs sont un exemple rayonnant du chrétien qui vit vraiment sa consécration baptismale, croît en cette vie qui lui a été donnée par le sacrement de l'initiation et que celui de la confirmation a renforcée de telle manière que la religion n'est pas pour lui un facteur marginal mais bien l'essence même de tout son être et de son action, faisant en sorte que la charité divine devient la force inspiratrice, active et agissante d'une existence toute tendue vers l'union d'amour avec Dieu et avec tous les hommes de bonne volonté, qui trouvera sa plénitude dans l'éternité.

L'Eglise et le monde d'aujourd'hui ont extrêmement besoin de tels hommes et de telles femmes, de toutes conditions et de tous états de vie, prêtres, religieux et laïcs, parce que seules les personnes de cette stature et de cette sainteté seront capables de changer notre monde tourmenté et de lui rendre, en même temps que la paix, cette orientation spirituelle et vraiment chrétienne à laquelle tout homme aspire intimement — même parfois sans s'en rendre compte — et dont nous avons tous tant besoin.

Que notre gratitude monte vers Dieu qui a voulu dans sa prévoyante bonté susciter ces saints martyrs dont l'action et le sacrifice ont contribué à la conservation de la foi catholique en Angleterre et dans le Pays de Galles.

Que le Seigneur continue à susciter dans l'Eglise, des laïcs, des religieux et des prêtres qui soient de dignes émules de ces hérauts de la foi.

Dieu veuille dans son amour que fleurissent et se développent même aujourd'hui des centres d'étude, de formation et de prière, aptes à préparer, dans les conditions modernes, de saints prêtres et des saints missionnaires tels que furent en ces temps les vénérables collèges de Rome et de Valladolid et les glorieux séminaires de Saint-Omer et de Douai, des rangs desquels sortirent justement beaucoup des quarante martyrs. Ainsi, comme le disait l'un d'entre eux, saint Edmond Campion, une grande personnalité : « Cette Eglise ne s'affaiblira jamais tant qu'il y aura des prêtres et des pasteurs à veiller sur leur troupeau ». Que le Seigneur veuille nous accorder la grâce qu'en ces temps d'indifférentisme religieux et de matérialisme théorique et pratique qui sévit toujours davantage, l'exemple et l'intercession des saints quarante martyrs nous réconfortent dans la foi et raffermissent notre amour authentique pour Dieu, pour son Eglise et pour tous les hommes.

SOURCE :

http://www.clerus.org/bibliaclerusonline/fr/itx.htm

Forty Martyrs of England and Wales (RM)

Died 16th and 17th centuries; canonized by Pope Paul VI in 1970. Each of the individual saints has his own feast day in addition to the corporate one today. The dates vary in the diocesan calendars of England and Wales. The forty are only a small portion of the many martyrs of the period whose causes have been promoted. All suffered for continuing to profess the Catholic faith following King Henry VIII's promulgation of the Act of Supremacy, which declared that the king of England was the head of the Church of England.

Most of them were hanged, drawn, and quartered--a barbaric execution, which meant that the individual was hanged upon a gallows, but cut down before losing consciousness. While still alive--and conscious, they were then ripped up, eviscerated, and the hangman groped about among the entrails until he found the heart--which he tore out and showed to the people before throwing it on a fire (Undset).

The list below gives very basic details. More information is given on the individual feast day listed.

Alban Bartholomew Roe--Benedictine priest (born in Suffolk; died at Tyburn, 1642) (f.d. January 21).

Alexander Briant--priest (born in Somerset, England; died at Tyburn, 1851) (f.d. December 1).

Ambrose Edward Barlow--Benedictine priest (born in Manchester, England, 1585; died at Lancaster, 1641) (f.d. September 10).

Anne Higham Line--widow, for harboring priests (born at Dunmow, Essex, England; died at Tyburn, 1601) (f.d. February 27).

Augustine Webster--Carthusian priest (died at Tyburn, 1535) (f.d. May 4).

Cuthbert Mayne--Priest (born in Youlston, Devonshire, England, 1544; died at Launceston, 1577) (f.d. November 30).

David Lewis--Jesuit priest, (born at Abergavenny, Monmouthshire, Wales, in 1616; died at Usk 1679) (f.d. August 27).

(Brian) Edmund Arrowsmith--Jesuit priest (born Haydock, England, 1584; died at Lancaster in 1628) (f.d. August 28).

Edmund Campion--Jesuit priest (born in London, England, c. 1540; died at Tyburn, 1581) (f.d. December 1).

Edmund Jennings (Genings, Gennings)-- priest (born at Lichfield, England, in 1567; died at Tyburn 1591) (f.d. December 10).

Eustace White--priest (born at Louth, Lincolnshire, England; died at Tyburn, 1591) (f.d. December 10).

Henry Morse--Jesuit priest (born at Broome, Suffolk, England, in 1595; died at Tyburn, 1645) (f.d. February 1).

Henry Walpole--Jesuit priest (born at Docking, Norfolk, England, 1558; died at York in 1595) (f.d. April 7).

John Almond--priest (born at Allerton, near Liverpool, England, 1577; died at Tyburn, 1612) (f.d. December 5).

John Boste--priest (born in Dufton, Westmorland, England, c. 1544; died at Dryburn near Durham, 1594) (f.d. July 24).

John Houghton--Carthusian priest (born in Essex, England, in 1487; died at Tyburn, 1535) (f.d. May 4).

John Jones (alias Buckley)--Friar Observant (born in Clynog Fawr, Carnavonshire, Wales; died at Southwark, London, in 1598) (f.d. July 12).

John Kemble--priest (born at Saint Weonard's, Herefordshire, England, in 1599; died at Hereford in 1679) (f.d. August 22).

John Lloyd--priest, Welshman (born in Brecknockshire, Wales; died in Cardiff, Wales, in 1679) (f.d. July 22).

John Paine (Payne)--priest (born at Peterborough, England; died at Chelmsford, 1582) (f.d. April 2).

John Plessington (a.k.a. William Pleasington)--priest (born at Dimples Hall, Lancashire, England; died at Barrowshill, Boughton outside Chester, England, 1679) (f.d. July 19).

John Rigby--household retainer of the Huddleston family (born near Wigan, Lancashire, England, c. 1570; died at Southwark in 1601) (f.d. June 21).

John Roberts--Benedictine priest, Welshman (born near Trawsfynydd Merionethshire, Wales, in 1577; died at Tyburn, 1610) (f.d. December 10).

John Southworth--priest (born in Lancashire, England, in 1592; died at Tyburn 1654) (f.d. June 28).

John Stone--Augustinian friar (born in Canterbury, England; died at Canterbury, c. 1539) (f.d. December 27).

John Wall--Franciscan priest (born in Lancashire, England, 1620; died at Redhill, Worcester, in 1679) (f.d. August 22).

Luke Kirby--priest (born at Bedale, Yorkshire, England; died at Tyburn, 1582) (f.d. May 30).

Margaret Middleton Clitherow--wife, mother, and school mistress (born in York, England, c. 1555; died at York in 1586) (f.d. March 25).

Margaret Ward--gentlewoman who engineered a priest's escape from jail (born in Congleton, Cheshire, England; died at Tyburn in 1588) (f.d. August 30).

Nicholas Owen--Jesuit laybrother (born at Oxford, England; died in the Tower of London in 1606) (f.d. March 2).

Philip Evans--Jesuit priest, (born in Monmouthshire, Wales, in 1645; died in Cardiff, Wales, in 1679) (f.d. July 22).

Philip Howard--Earl of Arundel and Surrey (born in 1557; died in the Tower of London, believed to have been poisoned, 1595) (f.d. October 19).

Polydore Plasden--priest (born in London, England; died at Tyburn, in 1591) (f.d. December 10).

Ralph Sherwin--priest (born at Rodsley, Derbyshire, England; died at Tyburn, 1851) (f.d. December 1).

Richard Gwyn--poet and schoolmaster; protomartyr of Wales (born at Llanidloes, Montgomeryshire, Wales, in 1537; died at Wrexham, Wales, in 1584) (f.d. October 17).

Richard Reynolds--Brigittine priest (born in Devon, England, c. 1490; died Tyburn in 1535) (f.d. May 4).

Robert Lawrence--Carthusian priest (died at Tyburn in 1535) (f.d. May 4).

Robert Southwell--Jesuit priest (born at Horsham Saint, Norfolk, England, c. 1561; died at Tyburn in 1595) (f.d. February 21).

Swithun Wells--schoolmaster (born at Bambridge, Hampshire, England, in 1536; died at Gray's Inn Fields, London, 1591) (f.d. December 10). Mrs. Wells was also condemned to death, but was reprieved and died in prison, 1600).

Thomas Garnet--Jesuit priest (born at Southwark, England; died at Tyburn, in 1608) (f.d. June 23).

Profile

§ Polydore Plasden

§ Swithun Wells

CANONIZZAZIONE DI QUARANTA MARTIRI DELL’INGHILTERRA E DEL GALLES

OMELIA DEL SANTO PADRE PAOLO VI

Domenica, 25 ottobre l970

We extend Our greeting first of all to Our venerable brother Cardinal John Carmel Heenan, Archbishop of Westminster, who is present here today. Together with him We greet Our brother bishops of England and Wales and of all the other countries, those who have come here for this great ceremony. We extend Our greeting also to the English priests, religious, students and faithful. We are filled with joy and happiness to have them near Us today; for us-they represent all English Catholics scattered throughout the world. Thanks to them we are celebrating Christ’s glory made manifest in the holy Martyrs, whom We have just canonized, with such keen and brotherly feelings that We are able to experience in a very special spiritual way the mystery of the oneness and love of .the Church. We offer you our greetings, brothers, sons and daughters; We thank you and We bless you.

While We are particularly pleased to note the presence of the official representative of the Archbishop of Canterbury, the Reverend Doctor Harry Smythe, We also extend Our respectful and affectionate greeting to all the members of the Anglican Church who have likewise come to take part in this ceremony. We indeed feel very close to them. We would like them to read in Our heart the humility, the gratitude and the hope with which We welcome them. We wish also to greet the authorities and those personages who have come here to represent Great Britain, and together with them all the other representatives of other countries and other religions. With all Our heart We welcome them, as we celebrate the freedom and the fortitude of men who had, at the same time, spiritual faith and loyal respect for the sovereignty of civil society.

STORICO EVENTO PER LA CHIESA UNIVERSALE

La solenne canonizzazione dei 40 Martiri dell’Inghilterra e del Galles da Noi or ora compiuta, ci offre la gradita opportunità di parlarvi, seppur brevemente, sul significato della loro esistenza e sulla importanza the la loro vita e la loro morte hanno avuto e continuano ad avere non solo per la Chiesa in Inghilterra e nel Galles, ma anche per la Chiesa Universale, per ciascuno di noi, e per ogni uomo di buona volontà.

Il nostro tempo ha bisogno di Santi, e in special modo dell’esempio di coloro che hanno dato il supremo testimonio del loro amore per Cristo e la sua Chiesa: «nessuno ha un amore più grande di colui che dà la vita per i propri amici» (Io. l5, l3). Queste parole del Divino Maestro, che si riferiscono in prima istanza al sacrificio che Egli stesso compì sulla croce offrendosi per la salvezza di tutta l’umanità, valgono pure per la grande ed eletta schiera dei martiri di tutti i tempi, dalle prime persecuzioni della Chiesa nascente fino a quelle – forse più nascoste ma non meno crudeli - dei nostri giorni. La Chiesa di Cristo è nata dal sacrificio di Cristo sulla Croce ed essa continua a crescere e svilupparsi in virtù dell’amore eroico dei suoi figli più autentici. «Semen est sanguis christianorum» (TERTULL., Apologet., 50; PL l, 534). Come l’effusione del sangue di Cristo, così l’oblazione che i martiri fanno della loro vita diventa in virtù della loro unione col Sacrificio di Cristo una sorgente di vita e di fertilità spirituale per la Chiesa e per il mondo intero. «Perciò - ci ricorda la Costituzione Lumen gentium (Lumen gentium, 42) – il martirio, col quale il discepolo è reso simile al Maestro che liberamente accetta la morte per la salute del mondo, e a Lui si conforma nell’effusione del sangue, è stimato dalla Chiesa dono insigne e suprema prova di carità».

Molto si è detto e si è scritto su quell’essere misterioso che è l’uomo : sulle risorse del suo ingegno, capace di penetrare nei segreti dell’universo e di assoggettare le cose materiali utilizzandole ai suoi scopi; sulla grandezza dello spirito umano che si manifesta nelle ammirevoli opere della scienza e dell’arte; sulla sua nobiltà e la sua debolezza; sui suoi trionfi e le sue miserie. Ma ciò che caratterizza l’uomo, ciò che vi è di più intimo nel suo essere e nella sua personalità, è la capacità di amare, di amare fino in fondo, di donarsi con quell’amore che è più forte della morte e che si prolunga nell’eternità.

IL SACRIFICIO NELL’AMORE PIÙ ALTO

Il martirio dei cristiani è l’espressione ed il segno più sublime di questo amore, non solo perché il martire rimane fedele al suo amore fino all’effusione del proprio sangue, ma anche perché questo sacrificio viene compiuto per l’amore più alto e nobile che possa esistere, ossia per amore di Colui che ci ha creati e redenti, che ci ama come Egli solo sa amare, e attende da noi una risposta di totale e incondizionata donazione, cioè un amore degno del nostro Dio.

Nella sua lunga e gloriosa storia, la Gran Bretagna, isola di santi, ha dato al mondo molti uomini e donne che hanno amato Dio con questo amore schietto e leale: per questo siamo lieti di aver potuto annoverare oggi 40 altri figli di questa nobile terra fra coloro che la Chiesa pubblicamente riconosce come Santi, proponendoli con ciò alla venerazione dei suoi fedeli, e perché questi ritraggano dalle loro esistenze un vivido esempio.

A chi legge commosso ed ammirato gli atti del loro martirio, risulta chiaro, vorremmo dire evidente, che essi sono i degni emuli dei più grandi martiri dei tempi passati, a motivo della grande umiltà, intrepidità, semplicità e serenità, con le quali essi accettarono la loro sentenza e la loro morte, anzi, più ancora con un gaudio spirituale e con una carità ammirevole e radiosa.

È proprio questo atteggiamento profondo e spirituale che accomuna ed unisce questi uomini e donne, i quali d’altronde erano molto diversi fra loro per tutto ciò che può differenziare un gruppo così folto di persone, ossia l’età e il sesso, la cultura e l’educazione, lo stato e condizione sociale di vita, il carattere e il temperamento, le disposizioni naturali e soprannaturali, le esterne circostanze della loro esistenza. Abbiamo infatti fra i 40 Santi Martiri dei sacerdoti secolari e regolari, abbiamo dei religiosi di vari Ordini e di rango diverso, abbiamo dei laici, uomini di nobilissima discendenza come pure di condizione modesta, abbiamo delle donne che erano sposate e madri di famiglia: ciò che li unisce tutti è quell’atteggiamento interiore di fedeltà inconcussa alla chiamata di Dio che chiese a loro, come risposta di amore, il sacrificio della vita stessa.

E la risposta dei martiri fu unanime: «Non posso fare a meno di ripetervi che muoio per Dio e a motivo della mia religione; - così diceva il Santo Philip Evans - e mi ritengo così felice che se mai potessi avere molte altre vite, sarei dispostissimo a sacrificarle tutte per una causa tanto nobile».

LEALTÀ E FEDELTÀ

E, come d’altronde numerosi altri, il Santo Philip Howard conte di Arundel asseriva egli pure: «Mi rincresce di avere soltanto una vita da offrire per questa nobile causa». E la Santa Margaret Clitherow con una commovente semplicità espresse sinteticamente il senso della sua vita e della sua morte: «Muoio per amore del mio Signore Gesù». « Che piccola cosa è questa, se confrontata con la morte ben più crudele che Cristo ha sofferto per me », così esclamava il Santo Alban Roe.

Come molti loro connazionali che morirono in circostanze analoghe, questi quaranta uomini e donne dell’Inghilterra e del Galles volevano essere e furono fino in fondo leali verso la loro patria che essi amavano con tutto il cuore; essi volevano essere e furono di fatto fedeli sudditi del potere reale che tutti - senza eccezione alcuna - riconobbero, fino alla loro morte, come legittimo in tutto ciò che appartiene all’ordine civile e politico. Ma fu proprio questo il dramma dell’esistenza di questi Martiri, e cioè che la loro onesta e sincera lealtà verso l’autorità civile venne a trovarsi in contrasto con la fedeltà verso Dio e con ciò che, secondo i dettami della loro coscienza illuminata dalla fede cattolica, sapevano coinvolgere le verità rivelate, specialmente sulla S. Eucaristia e sulle inalienabili prerogative del successore di Pietro, che, per volere di Dio, è il Pastore universale della Chiesa di Cristo. Posti dinanzi alla scelta di rimanere saldi nella loro fede e quindi di morire per essa, ovvero di aver salva la vita rinnegando la prima, essi, senza un attimo di esitazione, e con una forza veramente soprannaturale, si schierarono dalla parte di Dio e gioiosamente affrontarono il martirio. Ma talmente grande era il loro spirito, talmente nobili erano i loro sentimenti, talmente cristiana era l’ispirazione della loro esistenza, che molti di essi morirono pregando per la loro patria tanto amata, per il Re o per la Regina, e persino per coloro che erano stati i diretti responsabili della loro cattura, dei loro tormenti, e delle circostanze ignominiose della loro morte atroce.

Le ultime parole e l’ultima preghiera del Santo John Plessington furono appunto queste: «Dio benedica il Re e la sua famiglia e voglia concedere a Sua Maestà un prospero regno in questa vita e una corona di gloria nell’altra. Dio conceda pace ai suoi sudditi consentendo loro di vivere e di morire nella vera fede, nella speranza e nella carità».

«POSSANO TUTTI OTTENERE LA SALVEZZA»

Così il Santo Alban Roe, poco prima dell’impiccagione, pregò: «Perdona, o mio Dio, le mie innumerevoli offese, come io perdono i miei persecutori», e, come lui, il Santo Thomas Garnet che - dopo aver singolarmente nominato e perdonato coloro che lo avevano tradito, arrestato e condannato - supplicò Dio dicendo: «Possano tutti ottenere la salvezza e con me raggiungere il cielo».

Leggendo gli atti del loro martirio e meditando il ricco materiale raccolto con tanta cura sulle circostanze storiche della loro vita e del loro martirio, rimaniamo colpiti soprattutto da ciò che inequivocabilmente e luminosamente rifulge nella loro esistenza; esso, per la sua stessa natura, è tale da trascendere i secoli, e quindi da rimanere sempre pienamente attuale e, specie ai nostri giorni, di importanza capitale. Ci riferiamo al fatto che questi eroici figli e figlie dell’Inghilterra e del Galles presero la loro fede veramente sul serio: ciò significa che essi l’accettarono come l’unica norma della loro vita e di tutta la loro condotta, ritraendone una grande serenità ed una profonda gioia spirituale. Con una freschezza e spontaneità non priva di quel prezioso dono che è l’umore tipicamente proprio della loro gente, con un attaccamento al loro dovere schivo da ogni ostentazione, e con la schiettezza tipica di coloro che vivono con convinzioni profonde e ben radicate, questi Santi Martiri sono un esempio raggiante del cristiano che veramente vive la sua consacrazione battesimale, cresce in quella vita che nel sacramento dell’iniziazione gli è stata data e che quello della confermazione ha rinvigorito, in modo tale che la religione non è per lui un fattore marginale, bensì l’essenza stessa di tutto il suo essere ed agire, facendo sì che la carità divina diviene la forza ispiratrice, fattiva ed operante di una esistenza, tutta protesa verso l’unione di amore con Dio e con tutti gli uomini di buona volontà, che troverà la sua pienezza nell’eternità.

La Chiesa e il mondo di oggi hanno sommamente bisogno di tali uomini e donne, di ogni condizione me stato di vita, sacerdoti, religiosi e laici, perché solo persone di tale statura e di tale santità saranno capaci di cambiare il nostro mondo tormentato e di ridargli, insieme alla pace, quell’orientamento spirituale e veramente cristiano a cui ogni uomo intimamente anela - anche talvolta senza esserne conscio - e di cui tutti abbiamo tanto bisogno.

Salga a Dio la nostra gratitudine per aver voluto, nella sua provvida bontà, suscitare questi Santi Martiri, l’operosità e il sacrificio dei quali hanno contribuito alla conservazione della fede cattolica nell’Inghilterra e nel Galles.

Continui il Signore a suscitare nella Chiesa dei laici, religiosi e sacerdoti che siano degni emuli di questi araldi della fede.

Voglia Dio, nel suo amore, che anche oggi fioriscano e si sviluppino dei centri di studio, di formazione e di preghiera, atti, nelle condizioni di oggi, a preparare dei santi sacerdoti e missionari quali furono, in quei tempi, i Venerabili Collegi di Roma e Valladolid e i gloriosi Seminari di St. Omer e Douai, dalle file dei quali uscirono appunto molti dei Quaranta Martiri, perché come uno di essi, una grande personalità, il Santo Edmondo Campion, diceva: «Questa Chiesa non si indebolirà mai fino a quando vi saranno sacerdoti e pastori ad attendere al loro gregge».

Voglia il Signore concederci la grazia che in questi tempi di indifferentismo religioso e di materialismo teorico e pratico sempre più imperversante, l’esempio e la intercessione dei Santi Quaranta Martiri ci confortino nella fede, rinsaldino il nostro autentico amore per Dio, per la sua Chiesa e per gli uomini tutti.

PER L’UNITA DEI CRISTIANI

May the blood of these Martyrs be able to heal the great wound inflicted upon God’s Church by reason of the separation of the Anglican Church from the Catholic Church. Is it not one-these Martyrs say to us-the Church founded by Christ? Is not this their witness? Their devotion to their nation gives us the assurance that on the day when-God willing-the unity of the faith and of Christian life is restored, no offence will be inflicted on the honour and sovereignty of a great country such as England. There will be no seeking to lessen the legitimate prestige and the worthy patrimony of piety and usage proper to the Anglican Church when the Roman Catholic Church-this humble “Servant of the Servants of God”- is able to embrace her ever beloved Sister in the one authentic communion of the family of Christ: a communion of origin and of faith, a communion of priesthood and of rule, a communion of the Saints in the freedom and love of the Spirit of Jesus.

Perhaps We shall have to go on, waiting and watching in prayer, in order to deserve that blessed day. But already We are strengthened in this hope by the heavenly friendship of the Forty Martyrs of England and Wales who are canonized today. Amen.

© Copyright - Libreria Editrice Vaticana

CANONIZATION OF 40 ENGLISH AND WELSH MARTYRS

Paolo Molinari, S.J.

Who the Forty Martyrs are

The forty Martyrs are among the best known of the many Catholics who gave their lives in England and Wales during the 16th and 17th centuries owing to the fact that their religious convictions clashed with the laws of the State at that time.

As is known, King Henry VIII had proclaimed himself supreme head of the Church in England and Wales, claiming for himself and his successors power over his subjects also in spiritual questions. According to our Catholic faith, this spiritual supremacy is due only to the Vicar of Christ, the Roman Pontiff. The Blessed Martyrs, and with them many other Catholics, though they wished to be, and actually were, loyal subjects of the Crown in everything belonging to it legitimately according to the ideas of that time, refused for reasons of conscience to recognize the "spiritual supremacy" of the King and to obey the laws issued by the political power on purely spiritual questions such as Holy Mass, Eucharistic Communion and similar matters. This was what led many people to face and meet death courageously rather than act against their conscience and deny their Catholic faith as regards the spiritual Primacy of the Vicar of Christ and the dogma of the Blessed Sacrament. From the ecumenical point of view, it is extremely important to realize the fact, proved historical, that the Martyrs were not put to death as a result of internal struggles between Catholics and Anglicans, but precisely because they were not willing to submit to a claim of the State which is commonly recognized today as being illegitimate and unacceptable.

If—as has always been clearly recognized in the case of St. Thomas More—it would be a serious error to consider him a leading figure in the opposition between Catholics and Anglicans, whereas he must be considered a person who rose in defence of the rights of conscience against State usurpation, the same can be said of the 40 Martyrs, who died for exactly the same reasons.

And this is just what the Church intends to stress with their Canonization. It was and is her intention to hold up to the admiration not only of Catholics, but of all men, the example of persons unconditionally loyal to Christ and to their conscience to the extent of being ready to shed their blood for that reason. Owing to their living faith in Christ, their personal attachment to Him, their deep sharing of His life and principles, these persons gave a clear demonstration of their authentically Christian charity for men, also when—on the scaffold—they prayed not only for those who shared their religious convictions, but also for all their fellow-countrymen it; and in particular for the Head of the State and even for their executioners.

This firm attitude in defence of their own freedom of conscience and of their faith in the truth of the Primacy of Christ and of the Holy Eucharist is identical in all the 40 Martyrs. In every other respect, however, they are different as for example in their state in life, social position, education, culture, age, character and temperament, and in fact in everything that makes up the most typically personal qualities of such a large group of men and women. The group is composed, in fact, of 13 priests of the secular clergy, 3 Benedictines, 3 Carthusians, 1 Brigittine, 2 Franciscans, 1 Augustinian, 10 Jesuits and 7 members of the laity, including 3 mothers.

The history of their martyrdom makes varied and stimulating reading as the different characters are revealed, not without a touch of typically English humour.

The torments they underwent give an idea of their fortitude. The priests—for example—were hanged, and shortly after the noose had tightened round their neck they were drawn and quartered. In most cases the second operation took place when they were still alive, for they were not left hanging long enough to bring about their death, sometimes only for a very few seconds.

For the others—that is, those who were not priests—death by hanging was the normal procedure. But before their execution the Martyrs were usually cruelly tortured, to make them reveal the names of any accomplices in their "crime", which was having celebrated Holy Mass, having attended it or having given shelter to priests. In the course of the trial, and during the tortures, they were offered their life and freedom on condition they recognized the king (or the queen, according to the period), as head of the Church of England.

And here are some particular features that drive home to us the spirituality of these Martyrs and how they faced death.

Cuthbert Mayne, a secular priest, replied to a gaoler who came to tell him he would be executed three days later: "I wish I had something valuable to give you, for the good news you bring me...".

Edmund Campion, a Jesuit, was so pleased when taken to the place of execution that the people said about him and his companions: "But they're laughing! He doesn't care at all about dying...'.

Ralph Sherwin, the first of the martyrs from the English College in Rome had heavy chains round his ankles that rattled at every step he took. "I have on my feet—he wrote wittily to a friend of his—some bells that remind me, when I walk, who I am and to whom I belong. I have never heard sweeter music than this..." He was executed immediately after Campion; he piously kissed the executioner's hands, still stained with the blood of his fellow martyr.

Alexander Briant—the diocesan priest who entered the Society of Jesus shortly before his death—had made himself a little wooden cross during his imprisonment, and held it clasped tightly between his hands all the time, even during the trial. It was then, however that they snatched it away from him But he replied to the judge: "You can take it out of my hands, but not out of my heart". The cross was later bought by some Catholics and is now in the English College in Rome.

John Paine (a secular priest, whose death was long mourned in the whole of Chelmsford) kissed the gallows before dying; and Richard Gwyn, a layman helped the hangman, overcome with emotion, to put the rope round his neck Some strange and extremely revealing episodes are told about Gwyn. Once for example, when he was in prison he was taken in chains to a chapel and obliged to stand right under the pulpit where an Anglican preacher was giving a sermon. The prisoner then began to rattle his chains, making such a din that no one could hear a word of what was being said. Taken back again to his cell, he was approached by various Protestant ministers. One of them, who had a purple nose, wanted to dispute about the keys of the Kingdom of Heaven and asserted that God had given them also to him, not just to St. Peter. "There is a difference", Richard Gwyn retorted "St. Peter was entrusted with the keys of the Kingdom of Heaven, while the keys entrusted to you are obviously those of the beer cellar".

Cultured Elizabethan society has its representatives among the martyrs Swithun Wellswas one of them. He had travelled a great deal; he had also been in Rome, and knew Italian well. He was a sportsman, particularly fond of hunting. On his way to the gallows, he caught sight of an old friend among the crowd and said to him: 'Farewell, my dear! And farewell too, to our fine hunting-parties. Now I've something far better to do...". It was December 10th, 1591, and bitterly cold. When they stripped him, he turned to his main persecutor, Topcliffe, and said in a joking tone: "Hurry up, please Mr. Topcliffe. Are you not ashamed to make a poor old man suffer in his shirt in this cold?"

Catholic priests managed to exercise the ministry thanks to the precious collaboration of the faithful. who welcomed them and kept them hidden in their homes and facilitated the celebration of Holy Mass. As can well be understood, now and again some one would betray them. The Jesuit laybrother, Nicholas Owen, was famous for the many hiding-places he built in numerous houses all over England. Arrested and imprisoned in the Tower of London, he died while being brutally tortured.

Of the forty Martyrs, the one who underwent the most torture was Henry Walpole, a Jesuit priest. His exceptional physique resisted the most atrocious forms of torture for as many as 14 times, until the gallows put an end to his sufferings.

The following inscription can still be read in the Tower of London, in one of the cells in which the Martyrs were detained: "Quanto plus afflictionis pro Christo in hoc saeculo, tanto plus gloriae in futuro" (the more suffering for Christ in this life, the more glory in heaven). The words were carved by Philip Howard, Earl of Arundell. He was the queen's favourite when he made his appearance at court, at the age of 18, leading a dissolute life. At the age of 24, he happened to be present at a discussion between Campion and some Protestant ministers. The holy Jesuit's words made a deep impression on him; as a result he was converted to Catholicism. As he was about to flee to the continent. he was captured and thrown into prison. He spent eleven long years there, reading, praying and meditating. He was condemned to death, but the sentence was postponed by the Queen's intervention. He fell seriously ill and died in prison.

A curious fact happened to the Franciscan John Jones. At the time of his execution, the hangman found he had forgotten the rope. The martyr took advantage of the hour's wait to speak to the crowd and to pray.

What is most striking is the serenity with which they all met death. Some of them even made witty, humorous remarks.

Thus, for example the Benedictine; John Roberts, seeing that a fire was being lit to burn his entrails—after hanging and quartering—made the sally: "I see you are preparing us a hot breakfast!".

When someone shouted at the Jesuit Edmund Arrowsmith: "You've got to die, do you realize?", he replied calmly: "So have you, so have you, my good man...". It is testified that Alban Roe a Benedictine religious, was a very entertaining fellow. In spite of the torture that was inflicted on him in prison he found the courage to invite the wardens to play cards with him, telling funny stories. He gave all the money he had to the executioner to drink to his health, warning him not to get drunk, however.

Philip Evans, having found a particularly kind judge, was treated somewhat indulgently in prison, so much so that he could even play tennis. Well, it was just during a game that the news of his condemnation to death arrived. He continued to play, as if nothing had happened. Then he picked up his harp and began to play.

John Kemple, a secular priest, was the only one who always refused to go into biding. "I'm too old now—he would say—and it is better for me to spend the rest of my life suffering for my religion". Of course he was caught and arrested. Before he was hanged, he asked to be allowed to smoke his inseparable pipe. The executioner, who happened to be an old friend of his, was overcome with emotion when the moment came to carry out his task and showed his hesitation. Then it was the martyr who urged him on, saying: "My good Anthony, do what you have to do. I forgive you with all my heart...".

The martyrdom of Margaret Clitherow is particularly moving. She was accused "of having sheltered the Jesuits and priests of the secular clergy, traitors to Her Majesty the Queen"; but she retorted: "I have only helped the Queen's friends". Margaret knew that the court had decided to condemn her to death and, not wanting to make the jury accomplices in her condemnation, she refused the trial. The alternative was to be crushed to death. When the terrible sentence was passed, Margaret said: "I will accept willingly everything that God wills".

On Friday March 25th, 1588, at eight o'clock in the morning, Margaret, just thirty-three years old, left Ouse Bridge prison, barefooted, bound for Toll Booth, accompanied by two police superintendents, four executioners and four women friends; she carried on her arm a white linen garment. When she arrived at the dungeon, she knelt in front of the officials, begging that she should not be stripped, but her prayer was not granted. While the men looked away, the four pious women gathered round her and before Margaret lay down on the ground they spread over her body the white garment that the prisoner had brought with her for that purpose. Then her martyrdom began.

Her arms were stretched out in the shape of a cross, and her hands tightly bound to two stakes in the ground. The executioners put a sharp stone the size of a fist under her back and placed on her body a large slab onto which weights were gradually loaded up to over 800 pounds. Margaret whispered: "Jesus, have mercy on me". Her death agony lasted for fifteen minutes, then the moaning ceased, and all was quiet.

These brief remarks on some outstanding episodes of the martyrdom of the 40 Martyrs, and the quoting of some of the words they uttered at the gallows, are sufficient to show what was the ultimate reasons for their death and, at the same time, the sublimely Christian state of mind of these heroes of the faith.

The history of the Cause

The history of the Beatification and Canonization Cause of our forty blessed Martyrs is part of. the wider history of a host of Martyrs who shed their blood in defence of the Catholic religion in England, from the schism that began in the reign of Henry VIII down to the end of the 17th century.

As early as the end of 1642 the first steps were taken to initiate the canonical process, but owing to the persecutions that were still rife, this initiative had soon to be suspended Nevertheless the victims of the persecution continued to be considered and venerated as martyrs. The Cause to prove their martyrdom and the existence of their cult was presented in Rome only in the second half of the last century, that is, following upon the reconstitution of the Catholic hierarchy in England and Wales, which took place in 1850.

The Cause of 254 martyrs was introduced on December 9th, 1886, by Leo XIII. Shortly afterwards, on December 29th 1886, the cult of 54 martyrs was confirmed by special decree, then on May 13th, 1895, 9 others. Finally, with the Apostolic Letter Atrocissima tormenta passi on December 15th, 1929, Pius XI beatified 136 victims of this persecution, and on May 19th 1935 he solemnly canonized Cardinal John Fisher and Chancellor Thomas More.

In still more recent times, the Hierarchy of England and Wales, conscious of the deep devotion to the martyrs who on different occasions had been declared blessed by the apostolic See, and aware that this devotion was addressed especially to some of the most popular of them was induced by the requests of the faithful and the multiplicity of favours obtained, to promote the canonization not of the whole host of these martyrs, but of a limited group of them. Right from the beginning of the negotiations, the Canonization Cause of these Martyrs was entrusted by the Hierarchy of England and Wales to Fr. Paolo Molinari, Postulator General of the Society of Jesus and President of the College of Postulators. He in turn nominated as Assistant Postulators Father Philip Caraman and James Walsh of the English Province of the Society. When the former was put for some years at the disposal of the Bishop of Oslo for certain important tasks, Father Clement Tigar, S.J. took his place.

After patient and laborious work, the list of the 40 martyrs chosen was presented by Fr. Molinari to the Holy See on December 1st, 1960. After the usual practices the latter proceeded, on May 24th 1961, with the so-called re-opening of the Cause by means of the Decree <Sanctorum Insula>, issued by order of Pope John XXIII.

Eleven of these forty martyrs had been included among the blessed solely by a decree confirming their cult. It was now necessary, in view of the hoped-for canonization, to make a thorough historical re-examination of their martyrdom, which had not been done ex professo when the Positio super introductione causue was prepared last century. As is customary, this task was entrusted to the Historical Section of the Sacred Congregation of Rites. Availing itself essentially of the studies carried out under its direction by the General Postulation of the Society of Jesus and by the office of the English Vice-Postulation, it made a very favourable pronouncement on the material and formal martyrdom of the eleven Blessed in question. The other studies prescribed by law having been completed, His Holiness Paul VI signed the special Decree of the Declaratio Martyrii of these eleven Blessed Martyrs, on May 4th 1970. In preparing for this Decree, two volumes were published in English and in Italian respectively of the Positio super Martyrii et cultu ex officio concinnata (Official Presentation of Documents on Martyrdom and Cult) (Typis Polyglottis Vaticanis, 1968, pp. XLIV, 375 in folio) which in the judgment of international critics is a real model of scientific editing of old texts.

Miracles attributed to the Forty Blessed Martyrs

Even before the rehearing of the Cause, many reports of favours and apparently miraculous cures attributed to the intercession of our Blessed Martyrs, had come to the knowledge of the Catholic Hierarchy of England and Wales, which hastened to inform the competent Roman Authorities.

From the time when the Cause of the 40 Blessed Martyrs was reopened, the ecclesiastical Hierarchy called for a prayer campaign in all English dioceses. Its most outstanding manifestations were various pilgrimages to the shrines of the Martyrs, diocesan and interdiocesan rallies, and particularly "<Martyrs' Sunday>", the yearly celebration of the memory of these Martyrs by all dioceses and parishes.

As a result of the intensification of the devotion of the faithful and their prayers, a good many events took place which looked like miracles. Sufficient data were collected about them to induce the Archbishop of Westminster, then Cardinal William Godfrey, to send a description of 24 seemingly miraculous cases to the Sacred Congregation.

The most striking of these and of the others that continued to be notified to the Postulation were first examined with special care by doctors of high repute. On the basis of their answers, two cases were chosen and the usual Apostolic Proceedings were instituted, and the acts were sent to the Sacred Congregation of Rites in Rome.

In the meantime requests and pleas continued to arrive for the canonization of the 40 blessed Martyrs of England and Wales as soon as possible. His Holiness Paul VI, duly informed about the extremely favourable outcome of the discussion of the Medical Council regarding one of the two above-mentioned cases, and keeping in mind the fact that the blessed Thomas More and John Fisher, belonging to the same group of Martyrs, had been canonized with a dispensation from miracles, considered that it was possible to proceed with the Canonization on the basis of this one miracle, after further discussions at the S. Congregation for the Causes of Saints had taken place.

The same S. Congregation, having issued the special Decree on July 30th, 1969, proceeded with the examination of the miracle, that is, the cure of a young mother affected with a malignant tumour (fibrosarcoma) in the left scapula, a cure which the Medical Council had judged gradual, perfect, constant and unaccountable on the natural plane.

After due assessment of the case and the usual discussions within the S. Congregation for the Causes of Saints, which concluded with an extremely favourable result on May 4th, 1970, his Holiness Paul VI confirmed the preternatural character of this cure brought about by God at the intercession of the 40 blessed Martyrs of England and Wales.

From the point of view of canonical procedure, the way was now open for solemn Canonization if the Sovereign Pontiff so decided.

There still remained another problem, however, which had been carefully taken into account by the Postulation right from the beginning, but which now had to be solved on the basis of another thorough study, that is, the problem of the opportuneness of this Canonization. While in fact the vast majority of English Catholics—Bishops, clergy and laity—thorough study, that is, the problem of faith to be raised to the honours of the altar, some voices had been raised in repeated circumstances to say that canonization of these Martyrs might be inopportune for ecumenical reasons.

Opportuneness of the Canonization

In more recent times—November 1969—the Archbishop of Canterbury, Dr. Ramsey, had expressed his apprehension that this Canonization might rekindle animosity and polemics detriment to the ecumenical spirit that has characterized the efforts of the Churches recently. But the reaction of the press, lay, Anglican and Catholic, showed clearly that this concern—though shared by some Anglicans and Catholics—did not correspond to the view of the vast majority. Many people, in fact, both Anglicans and Catholics, were aware of the fact that, right from the beginning of the re-opening of the Cause, the policy of its Promoters had been characterized by an extremely serene and ecumenical note; what is more, they realized the positive repercussions it offers just in this field if it is presented in this very spirit.

Right from the first announcement of the Re-opening of the Cause of the 40 Martyrs, decreed by Pope John XXIII on 24 May 1961, the Hierarchy of England and Wales let it be clearly under stood that nothing was further from the intentions of the Bishops than to stir up bad feelings and quarrels of the past.

The aim of the Postulator General Paolo Molinari S.J. and his collaborators, James Walsh S.J., Philip Caraman S.J. and Clement Tigar S.J., while they were carrying out the historical research and investigation, was to ensure that the Cause would be presented in an authentically ecumenical way.

For this reason the Postulator General, always working in close contact with the authorities of the S. Congregation that deals with the Causes of Saints and in agreement with the Hierarchy of England and Wales, asked Cardinal Agostino Bea, then President of the Secretariat for the Union of Christians, to act as the Cardinal Ponens of the Cause Aware of its ecumenical significance, he sustained, promoted and encouraged its course until he died. After his death the Secretariat itself continued to follow attentively the individual phases of the Cause and not only did not find any contrary motive but collaborated skillfully to ensure that the approach would benefit the ecumenical cause, instead of hampering it. (See in this connection the address that the present President of the Secretariat, Card. Willebrands, delivered in the Anglican cathedral in Liverpool during his recent visit to England).

The vast majority of people understood all this. The most authoritative voice in this sense was that of the British Council of Churches, which made a public declaration on the matter on December 17th, 1969. Not only does it recognize the importance for the Catholic Church to venerate its Martyrs, to whom the survival of the Catholic Church in England and Wales is essentially due, but it also expressed satisfaction that the various Christian denominations are united today in recognizing the tradition of the Martyrs as a common element from which we must all draw strength disregarding denominational frontiers.

Quite a few authoritative persons—including several Anglican Bishops—keeping in mind and appreciating the actions of considerable ecumenical value of Pope Paul VI on various occasion—expressed the view and the hope that the Canonization of the 40 Martyrs might be an opportunity for the members of other Christian denominations to make a positive gesture that would funkier the cause of union, by joining in the admiration of Catholics for these Martyrs.

Ecumenical exchanges

Some months before the Consistory the General Postulation, as well as the Vice-Postulation, had charged specialized agencies with following the whole national and provincial press of England and Wales, together with the European and American press, and sending it constantly everything that was published in connection with the Cause. At the same time it redoubled its efforts to obtain the widest and most accurate information not only on the attitude of English and Welsh Catholics, but above all on that of the Anglicans, with many of whose best qualified representatives there had long existed relations marked by sincere and brotherly frankness and a genuine spirit of mutual understanding and collaboration. The Hierarchy of England and Wales, in its turn, and in the first place Card. Godfrey's successor, His Eminence Card. Heenan, Vice-President of the Secretariat for the Union of Christians, made a point of establishing and maintaining exchanges of views with the competent authorities of the various Christian denominations in their country.

On the basis of this huge mass of material, it was established beyond al] shadow of doubt that at least 85 per cent of what had been printed in England and Wales, both on the Catholic and the non-Catholic side, far from being unfavourable to the Cause, was clearly in favour of it or at least showed great understanding for the opportuneness of the canonization. This applies to publications such as "Church Times", or the "Church of England Newspaper." and the most widely read English national papers such as "The Times", "The Guardian", "The Economist", "The Spectator""The Daily Telegraph", "The Sunday Times" and many others.

On the other hand some foreign publications—including some well-known papers of protest—raised difficulties. It was at once clear, however, that these were based on insufficient knowledge of the complicated historical situation in which the Martyrs sacrificed their lives, and, to an even greater degree, of the present ecumenical situation in England. The latter calls for at least a minimum of concrete knowledge and cannot easily be understood by those who do not take the trouble to study it thoroughly Of course, everything possible has been done, by means of press conferences and other opportune methods, to eliminate this type of misunderstanding, generally most successfully.

A serious, serene and objective study of the whole situation led to the conclusion, therefore, that besides the numerous reasons clearly in favour of the canonization of the 40 blessed Martyrs, there were no real ecumenical objections to it, on the contrary the canonization offered considerable advantages also from the genuinely ecumenical point of view.

It was precisely these ideas that His Holiness Paul VI expressed and explained in a masterly fashion in the address he delivered on the occasion of the Consistory on May 18th, 1970, in which he announced his intention to proceed with the solemn canonization of the 40 blessed Martyrs of England and Wales on October 25th, 1970. In this address the Holy Father, besides pointing out, with serene frankness and great charity, the ecumenical value of this Cause, also laid particular stress on the fact that we need the example of these Martyrs particularly today not only because the Christian religion is still exposed to violent persecution in various parts of the world, but also because at a time when the theories of materialism and naturalism are constantly gaining ground and threatening to destroy the spiritual heritage of our civilization, the forty Martyrs—men and women from all walks of life—who did not hesitate to sacrifice their lives in obedience to the dictates of conscience and the divine will, stand out as noble witnesses to human dignity and freedom.

This declaration of the Sovereign Pontiff was received with practically unanimous approval, which showed how right the decision had been to proceed with the canonization. His address was given a great deal of attention and certainly contributed effectively to dispelling any doubts that may still have existed in certain quarters.

At the same time the Pope's words drive home to us unmistakably why the Church continues to propose new Saints. The formal recognition of the holiness of some of her members has the aim of presenting to the faithful and to all men the unshaken loyalty with which they followed Christ and his law. It aims at letting us have, in a living and existential way, the message that God addressed to us in his Son, who came on earth to make us share his life and his love. It aims at making us understand that, by welcoming his teaching and receiving Christ our Lord with sincere hearts we already become participants in that life that will be granted to us in its fullness when, having finished the course of our earthly existence after being faithful to Him, we are admitted to his presence (cfr. Lumen Gentium, 48).

Through these Saints it is God himself who is speaking to us and helping us to understand how, in the shifting circumstances of life, we must live our union with Him more and more intensely and thus grow in holiness:

"For when we look at the lives of those who have faithfully followed Christ, we are inspired with a new reason for seeking the city which is to come (Heb. 13:14; 11:10). At the same time we are shown a most safe path by which among the vicissitudes of this world and in keeping with the state in life and condition proper to each of us, we will be able to arrive at perfect union with Christ, that is, holiness. In the lives of those who shared in our humanity and yet were transformed into especially successful images of Christ (cf. 2 Cor. 3:18), God vividly manifests to men His presence and His face. He speaks to us in them, and gives us a sign of His kingdom, to which we are powerfully drawn, surrounded as we are by so many witnesses (cf. Heb. 12:1), and having such an argument for the truth of the gospel" (Lumen Gentium, No. 50).

The situations in which we live may vary, but in the last analysis they have a deep element in common which transcends time and circumstances. At the root of our existence there is God's invitation, his offer to open our hearts to his love and respond in our lives with authentic responsibility and consistency, to the claims of the love of Him who gave his life for us

Taken from:

L'Osservatore Romano

Weekly Edition in English

29 October 1970

L'Osservatore Romano is the newspaper of the Holy See.

The Weekly Edition in English is published for the US by:

The Cathedral Foundation

L'Osservatore Romano English Edition

320 Cathedral St.

Baltimore, MD 21201

Subscriptions: (410) 547-5324

Fax: (410) 332-1069

lormail@catholicreview.org

The image here is of St Margaret Clitherow, the “pearl of York”, a married woman who held Masses in her house and sheltered priests. She suffered a horrific death. For details of her life and death, see 26th March. Here Patrick Duffy gives the details of the lives and deaths of each of the Forty Martyrs of England and Wales.

3 Carthusians:

The Carthusians were all priors of different Charterhouses houses of the Carthusian Order). Summoned in 1535 by Secretary of State Thomas Cromwell to sign the Oath of Supremacy, they declined and by virtue of their Carthusian vow of silence refused to speak in their own defence.

Augustine Webster was educated at Cambridge and was prior of the Carthusian house of Our Lady of Melwood at Epworth, on the Isle of Axholme, North Lincolnshire in 1531.

John Houghton was born c. 1486 and educated at Cambridge. He joined the London Charterhouse in 1515. In 1531, he became abbot of the Charterhouse of Beauvale in Nottinghamshire but was then elected Prior of the London house, to which he returned.

Robert Lawrenceserved as prior of the Charterhouse at Beauvale, Nottinghamshire.

The three were cruelly tortured and executed at Tyburn, making them among the first martyrs from the order in England. They were beatified in 1886.

1 Augustinian friar: John Stone d. 1538

John Stone was a doctor of theology living in the Augustinian friary at Canterbury. He publicly denounced the behaviour of King Henry VIII from the pulpit of the Austin Friars and publicly stated his approval of the status of monarch’s first marriage – clearly opposing the monarch’s wish to gain a divorce. In 1538, in consequence of the Act of Supremacy, Bishop Richard Ingworth (a former Dominican, and by then Bishop of Dover) visited the Canterbury friary as part of the process of the dissolution of monasteries in England. Ingworth commanded all of the friars to sign a deed of surrender by which the King should gain possession of the friary and its surrounding property. Most did, but John Stone refused and even further denounced bishop Ingworth for his compliance with the King’s desires. He was executed at the Dane John (Dungeon Hill), Canterbury, for his opposition to the King’s wishes.

1 Brigittine: Richard Reynolds 1492-1535

The Brigittines were an order of monks founded by St Bridget of Sweden.

Richard was born in Devon in 1492 and educated at Cambridge. In 1513, he entered the Brigettines at Syon Abbey, Isleworth. When Henry VIII demanded royal oaths, Richard was along with the Carthusian priors who were hanged, drawn and quartered at Tyburn Tree in London after being dragged through the streets in 1535.

Two Franciscans

John Jones

(Friar Observant – also known as John Buckley, John Griffith, or Godfrey Maurice)

John Jones was from a good Welsh and strongly Catholic family. As a youth, he entered the Observant Franciscan convent at Greenwich; at its dissolution in 1559 he went to the Continent, and took his vows at Pontoise, France. After many years, he journeyed to Rome, where he stayed at the Ara Coeli convent of the Observants (A branch of the Franciscan Order of Friars Minor that followed the Franciscan Rule literally) . There he joined the Roman province of the Reformati (a stricter observance branch of the Order of Friars Minor). In 1591, he requested to return on mission to England. His superiors, aware that such a mission usually ended in death, consented and John also received a special blessing and commendation from Pope Clement VIII.

Reaching London at the end of 1592, he stayed temporarily at the house which Father John Gerard SJ had provided for missionary priests; he then laboured in different parts of the country. His brother Franciscans in England elected him their provincial. In 1596 a notorious priest catcher called Topcliffe had him arrested and imprisoned for nearly two years. During this time he met, and helped sustain in his faith, John Rigby. On 3 July 1598 Father Jones was tried on the charge of “going over the seas in the first year of Her majesty’s reign (1558) and there being made a priest by the authority from Rome and then returning to England contrary to statute” . He was convicted of high treason and sentenced to being hanged, drawn, and quartered.

The execution was to take place in the early morning at St. Thomas’ Watering, in what is now the Old Kent Road, at the site of the junction of the old Roman road to London with the main line of Watling Street. Such ancient landmarks had been immemorially used as places of execution, Tyburn itself being merely the point where Watling Street crossed the Roman road to Silchester. The executioner had forgotten his ropes! In the delay while the forgetful man went to collect his necessary ropes John Jones took the opportunity to talk to the assembled crowd. He explained the important distinction – that he was dying for his faith alone and had no political interest. His dismembered remains were exposed, but were removed by some young Catholic gentlemen, one of whom suffered a long imprisonment for this offence. One of the relics eventually reached Pontoise, where the martyr had taken his religious vows.

John Wall 1620-79

Franciscan (known at Douay and Rome as John Marsh, and other aliases while on the mission in England)

Born in Preston, Lancashire, 1620, the son of wealthy and staunch Catholics, he was sent at a young age to Douai College. He entered the Roman College in 1641 and was ordained in 1645. Sent on mission in 1648, he received the habit of St. Francis at St. Bonaventure’s Friary, Douai in 1651 and a year later was professed, taking the name of Joachim of St. Anne. He filled the offices of vicar and novice master at Douai until 1656, when he returned to the Mission, and for twenty years ministered in Worcestershire. Captured in December 1678 at Rushock Court near Bromsgrove, where the sheriff’s man came to seek a debtor. When it was discovered he was a priest, he was asked to take the Oath of Supremacy and when he refused was put in Worcester Gaol

Sent on to London, he was four times examined by Oates, Bedloe, and others in the hope of implicating him in the pretended plot; but was declared innocent of all plotting and could have saved his life if he would abjure his religion. Brought back to Worcester, he was executed at Redhill on 22 August 1679. The day previous, William Levison was enabled to confess and communicate him, and at the moment of execution the same priest gave him the last absolution. His quartered body was given to his friends, and was buried in St. Oswald’s churchyard.

3 Benedictines

Alban Roe 1582-1642

Born Bartholemew Roe 1583 in Bury, St Edmunds, Suffolk. After meeting an imprisoned Catholic recusant, he converted to Catholicism. He spent some time at the English College at Douai in northern France, but was expelled for insubordination. He spent the rest of his novitiate at the Abbey of St. Lawrence, Dieulouard, a newly opened Benedictine house near Nancy – the home of Benedictine monks fleeing persecution in England. He was ordained priest there in 1612. Sent back to England, he was banished in 1615 but returned in 1618 and was imprisoned until 1623, when his release and re-exile was organised by the Spanish Ambassador. He returned two years later for the last time and was imprisoned for seventeen years. He was hanged, drawn and quartered at Tyburn on the 21st of January 1642.

Ambrose Barlow 1585-1641

Born Edward Barlow at Handforth Hall, Cheshire. Until 1607 he belonged to the Anglican church, but then turned to the Catholic church. He was educated at the Benedictine monastery of St. Gregory in Douai, France, and entered the English College in Valladolid, Spain, in 1610. He later returned to Douai where his elder brother (William) Rudesind Barlow was a professed monk. Barlow also professed in 1614 and was ordained a priest in 1617. Sent to England on mission in South Lancashire, he lived with protecting families near Manchester. But he was pursued for proselytising, imprisoned five times and released, but was finally arrested on Easter Sunday 1641. Paraded at the head of his parishoners, dressed in his surplice, and was followed by some 400 men armed with clubs and swords, he could have escaped in the confusion, but he voluntarily gave himself up. Imprisoned in Lancaster Castle for four months, he was sentenced after confessing to being a Catholic priest. On Friday September 10 he was hanged, drawn and quartered at Lancaster on 10th September 1641. Many of his relics are preserved, a hand being at Stanbrook Abbey near Worcester and his skull in Wardley Hall.

John Roberts 1575-1606

John was born in 1575 the son of John and Anna Roberts of Trawsfynydd, Merionethshire, Wales. He matriculated at St. John’s College, Oxford, in February 1595 but left after two years without taking a degree and went as a law student at one of the Inns of Court. In 1598 he travelled on the continent and in Paris. Through the influence of a Catholic fellow-countryman he was converted and on the advice of John Cecil, an English priest who afterwards became a Government spy, he decided to enter the English College at Valladolid in 1598.

The following year he went to the Abbey of St Benedict, Valladolid, and from there he was sent for his novitiate to the Abbey of St. Martin at Compostella where he was professed in 1600. After completing his studies he was ordained and set out for England on the 26 December 1602. Arriving in April 1603, he was arrested and banished on 13th May. He reached Douai on 24 May and soon returned to England where he ministered among the plague-stricken people in London. In 1604, while embarking for Spain with four postulants, he was again arrested. Not being recognised as a priest, he was soon released and banished, but he returned to England at once. On 5 November, 1605, while the house of Mrs. Percy, first wife of the Thomas Percy who was involved in the Gunpowder Plot was being searched, he found Roberts there and arrested him. Though acquitted of any complicity in the plot itself, Roberts was imprisoned in the Gatehouse at Westminster for seven months and then exiled anew in July 1606.

He now founded and became the first prior of the English Benedictine house at Douai for monks who had entered various Spanish monasteries. This was the beginning of the monastery of St. Gregory at Douai and this community of St. Gregory’s still exists at Downside Abbey, near Bath, England, having settled in England in the 19th century.

In October 1607, Roberts returned to England and in December was yet again arrested and again contrived to escape after some months and lived for about a year in London, again travelling to Spain and Douai in 1608. Returning to England within a year, knowing that his death was certain if he were again captured, he was in fact captured on 2nd December 1610 just as he was concluding Mass. Taken to Newgate in his vestments, he was tried and found guilty under the Act forbidding priests to minister in England, and on 10th December was hanged, drawn, and quartered at Tyburn. His body was taken and buried in St. Gregory’s, Douai, but disappeared during the French Revolution. Two fingers are still preserved as relics at Downside and Erdington Abbeys respectively and a few minor relics exist.

10 Jesuits

Alexander Briant 1556-81

Alexander was born in Somerset about 1556 and at an early age entered Hart Hall, Oxford, where he met a Jesuit priest and became a Catholic. He then went to the English college at Reims and was ordained priest there in 1578. He returned to England and ministered in in his home county of Somersetshire. Arrested in 1581, he was taken to London and seriously tortured, though in a letter to his Jesuit companions he said he felt no pain and wondered if this were miraculous. He was barely twenty five when he was executed at Tyburn.

Edmund Campion 1540-81

Son of a Catholic bookseller named Edmund whose family converted to Anglicanism, he planned to enter his father’s trade, but was awarded a scholarship to Saint John’s College, Oxford under the patronage of Queen Elizabeth I’s court favorite, Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester. A much sought-after speaker, he was being spoken as a possible Archbishop of Canterbury. Queen Elizabeth offered him a deaconate in the Church of England, but he declined the offer. Instead he went to Ireland to take part in the proposed establishment of the University of Dublin. Here he enjoyed the protection of of Lord Deputy Sir Henry Sidney and the friendship of Sir Patrick Barnewell at Turvey. While in Ireland he wrote a history of Ireland (first published in Holinshead’s Chronicles).

In 1571 he left Ireland secretly and went to Douai where he was reconciled to the Catholic Church and received the Eucharist that he had denied himself for the previous 12 years. He entered the English College founded by William Allen, another Oxford religious refugee. After obtaining his degree in divinity, he walked as a pilgrim to Rome and joined the Jesuits. Ordained in 1578, he spent some time working in Prague and Vienna. He returned to London as part of a Jesuit mission, crossing the Channel disguised as a jewel merchant, and worked with Jesuit brother Nicholas Owen. He led a hunted life, preaching and ministering to Catholics in Berkshire, Oxfordshire, Northamptonshire, and Lancashire. At this time also he wrote his Decem Rationes (“Ten Reasons”) against the Anglican Church, 400 copies of which found their way to the benches of St Mary’s, Oxford, at the Commencement, on June 27, 1581.

Captured by a spy, Campion was taken to London and committed to the Tower. Charged with conspiring to raise a sedition in the realm and dethrone the Queen he was found guilty. Campion replied: “If our religion do make traitors we are worthy to be condemned; but otherwise are and have been true subjects as ever the queen had. In condemning us, you condemn your own ancestors, you condemn all the ancient Bishops and Kings, you condemn all that was once the glory of England….” After spending his last days in prayer, was led with two companions to Tyburn and hanged, drawn and quartered on December 1, 1581.

Robert Southwell 1561-95