Saint Botolf

(✝ 655)

ou Botulphe.

Originaire de Maestricht, il fut converti alors que son pays était encore païen. Il passa alors en Belgique, puis en Angleterre, pour trouver un lieu désertique et mieux se consacrer à Dieu. Les invasions danoises détruisirent son ermitage. Il fut très honoré en Angleterre, jusqu'au jour où celle-ci quitta l'Église romaine.

Botulph, OSB Abbot (AC)

(also known as Botulf, Botolph)

Died c. 680; feast of his translation is December 1. Botulph and his brother, Saint Adulph, were two noble English brothers at the dawn of Christianity on that island. They were probably born in East Anglia. At some point they traveled into Belgian Gaul to learn more about Christian discipline in a monastery because they were then scarce in England. They progressed in the spiritual life to the point that Adulph is said to have been raised to the episcopate, though this is questioned. Botulph is said to have been chaplain to the convent where two of his king's sisters lived, possibly at Chelles. (Liobsynde, the first abbess of Wenlock (Salop), was from Chelles and Wenlock was initially dependent on Ikanhoe.)

Botulph returned to England with the treasure he had found and begged King Ethelmund of the South Saxons for land on which to set it. The king gave him the wilderness of Ikanhoe (Icanhoh), formerly thought to be near Boston (Botulf's stone) in Lincolnshire but now believed to be Iken in Suffolk. (Others relate that the land was provided by the king of East Anglia, either Ethelhere, 654, or more likely Ethelwold, 654-64.) There he built an abbey and taught the assembled brethren the rules of Christian perfection and the institutes of the holy fathers. He became one of the foremost missionaries of the 7th century.

Everyone loved Botulph: He was humble, mild, and affable. He always practiced what he preached, finding an upright example far more important than sermons. Nevertheless, Saint Ceolfrid travelled all the way from Wearmouth to converse with this man "of remarkable life and learning" before joining Saint Benedict Biscop at Wearmouth. Botulph thanked God in good times and in bad, knowing that God works all things to the good of those who love Him. He lived to a venerable age and was purified by a long illness before his happy death

Although his monastery was destroyed by the Danes, his relics were carried to Ely (the head) and Thorney Abbeys. It is said that when Ethelwold sent his disciple Ulfkitel to collect the relics of Botulph for Thorney Abbey, he found that he could not move them without also taking those of Adulph as well. Saint Edward the Confessor gave some of them to Westminster and others are at Bury Saint Edmunds. More than 70 English churches were dedicated to Saint Botulph, including four parishes in London. Name other place names also recall his sanctity including the town of Boston in Lincolnshire and Botulph's bridge, now Bottle-bride, in Huntingdonshire (Attwater, Benedictines, Farmer, Husenbeth).

In art, Saint Adulph, bishop, and Saint Botulf, abbot, hold the Abbey of Ikanhoe, Suffolk, England. The four gates of the City of London are dedicated to them (Roeder).

June 17

St. Botulph, Abbot

SS. BOTULPH and ADULPH were two noble English brothers who opened their eyes to the light of faith in the first dawning of the day of the gospel upon our ancestors. Astonished at the great truths which they had learned and penetrated with the most profound sentiments which religion inspires, they travelled into the Belgic Gaul there to find some religious houses and schools of virtue, which were then scarce in England. Such was the progress of these holy men that they soon were judged fit to be themselves masters. Nor was it long before Adulph was advanced to the bishopric of Maestricht, which he administered in so holy a manner, that he is honoured in France among the saints on the 17th of June. St. Botulph returned to England to bring to his own country the treasure he had found. Addressing himself to king Ethelmund he begged some barren spot of ground to found a monastery. The king gave him the wilderness of Ikanho, where he built an abbey, and taught the brethren whom he assembled there the rules of Christian perfection, and the institutes of the holy fathers. He was beloved by every one, being humble, mild and affable. All his discourse was on things which tended to edification, and his example was still far more efficacious to instil the true spirit of every virtue. When he was oppressed with any sickness he never ceased thanking and praising God with holy Job. Thus he persevered to a good old age. He was purified by a long illness before his happy death, which happened in the same year with that of St. Hilda, 655. His monastery having been destroyed by the Danes, his relics were carried, part to the monastery of Ely, and part to that of Thorney. St. Edward the Confessor afterwards bestowed some portion of them on his own abbey of Westminster. Few English saints have been more honoured by our ancestors. Four parishes in London, and innumerable others throughout the country bear his name. Botulph’s town, now Boston, in Lincolnshire, and Botulph’s bridge, now Bottle-bridge, in Huntingdonshire, are so called from him. Leland and Bale will have his monastery of Ikanho to have been in one of those two places; Hickes says at Boston; others think it was towards Sussex; for Ethelmund seems to have been king of the South-Saxons. Thorney abbey was situated in Cambridgeshire, and was one of those whose abbots sat in parliament. It was founded in 972 in honour of St. Mary and St. Botulph. In its church lay interred St. Botulph, St. Athulf, St. Huna, St. Tancred, St. Tothred, St. Hereferth, St. Cissa, St. Bennet, St. Tova or Towa, to whose memory a fair chapel called Thoueham, half a mile off in the wood, was consecrated. Thorney was anciently called Ancarig, that is, the Isle of Anchorets. Part of the relics of St. Botulph was kept at Medesham, afterwards called Peterburgh. See Dr. Brown Willis, on mitred Abbeys, t. 1, p. 187, and the life of St. Botulph published by Mabillon, Act. Ben. t. 3, p. 1, and by Papebroke, t. 3, Junij, p. 398. The anonymous author of this piece declares he had received some things which he relates from the disciples of the saint who had lived under his direction. There is also in the Cottonian library, n. 111, a MS. life of St. Botulph compiled by Folcard, first a monk of St. Bertin’s at St. Omer, afterwards made by the Conqueror abbot of Thorney in 1068. See also Narratio de Sanctis qui in Anglia quiescunt, translated from the English-Saxon into Latin by Francis Junius, and published by Dr. Hickes, Diss. Epist. pp. 118, 119. Thesauri, t. 1.

Rev. Alban Butler (1711–73). Volume VI: June. The Lives of the Saints. 1866.

St. Botulph

(Or BOTOLPH.)

Abbot, date of birth unknown; died c. 680. St. Botulph, the saint whose name is perpetuated in that of the American city of Boston, Massachusetts, was certainly an historical personage, though the story of his life is very confused and unsatisfactory. What information we possess about him is mainly derived from a short biography by Folcard, monk of St. Bertin and Abbot of Thorney, who wrote in the eleventh century (Hardy, Catalogue of Brit. Hist., I, 373). According to him Botulph was born of noble Saxon parents who were Christians, and was sent with his brother Adulph to the Continent for the purpose of study. Adulph remained abroad, where he is stated to have become Bishop of Utrecht, though his name does not occur in any of the ancient lists. Botulph, returning to England, found favour with a certain Ethelmund, "King of the southern Angles", whose sisters he had known in Germany, and was by him permitted to choose a tract of desolate land upon which to build a monastery. This place, surrounded by water and called Icanhoe (Ox-island), is commonly identified with the town of Boston in Lincolnshire, mainly on account of its name (Boston=Botulph's town). There is, however, something to suggest that the true spot may be the village of Iken in Suffolk which of old was almost encircled by the little river Alde, and in which the church is also dedicated to St. Botulph. In favour of Lincolnshire must be reckoned the fact that St. Botulph was much honoured in the North and in Scotland. Thus his feast was entered in the York calendar but not in that of Sarum. Moreover, even Folcard speaks of the Scots as Botulph's neighbours (vicini). In favour of Suffolk, on the other hand, may be quoted the tradition that St. Botulph, who is also called "bishop", was first buried at Grundisburgh, a village near Woodbridge, and afterwards translated to Bury St. Edmunds. This, however, may be another person, since he is always closely associated with a certain St. Jurmin (Arnold, Memorials of Bury, I, 352). That Botulph really did build a monastery at Icanhoe is attested by an entry in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle under the year 654: Botulf ongan thæt mynster timbrian æt Yceanho, i.e. Botulph began to build the minster at Icanhoe. That the saint must have lived somewhere in the Eastern counties is proved by the indisputable evidence of the "Historia Abbatum" (Plummer's Bede, I, 389), where we learn that Ceolfrid, Bede's beloved master at Wearmouth, "journied to the East Angles in order that he might see the foundation of Abbot Botulphus, whom fame had proclaimed far and wide to be a man of remarkable life and learning, full of the grace of the Holy Spirit", and the account goes on to say that Ceolfrid "having been abundantly instructed, so far as was possible in a short time, returned home so well equipped that no one could be found more learned than he either in ecclesiastical or monastic traditions". Folcard represents St. Botulph as living and dying at Icanhoe in spite of the molestations of the evil spirits to which he was exposed at his first coming. Later accounts, e.g. the lessons of the Schleswig Breviary, suppose him to have changed his habitation more than once and to have built at one time a monastery upon the bank of the Thames in honour of St. Martin. His relics are said after the incursions of the Danes to have been recovered and divided by St. Aethelwold between Ely, Thorney Abbey, and King Edgar's private chapel. What is more certain is that St. Botulph was honoured by many dedications of churches, over fifty in all, especially in East Anglia and in the North. His name is perpetuated not only by the little town of Boston in Lincolnshire with its American homonym, but also by Bossal in Yorkshire, Botesdale in Suffolk, Botolph Bridge in Huntingdonshire, and Botolph in Sussex. In England his feast was kept on 17 June, in Scotland on 25 June.

Sources

STANTON, Menology, 271; Acta SS., June, III, 402; MABILLON, Acta SS. Benedict., III, 1; STUBBS in Dict. Christ. Biog.; GRANT, in Dict. Nat. Biog.; FORBES, Calendars of Scottish Saints(Edinburgh, 1872), 283; and especially ARNOLD-FORSTER, Church Dedications(London, 1899), II, 52-56.

Thurston, Herbert. "St. Botulph." The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 2. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1907. 17 Jun. 2015 <http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/02709a.htm>.

Botulphis a popular medieval saint whose name has been honoured in the dedication of many East Anglian churches. Owen Spencer-Thomas tells the story of this Saxon saint.

Botulph was one of the most popular British saints of the early Middle Ages. He was a nobleman who went to the Continent to become a Benedictine monk and returned to England to found a monastery in East Anglia. Although the life story of this humble affable man is sketchy, records show that he did exist in history and his story is more fact than legend.

Born into a Christian Saxon family in the early seventh century, Botulph and his brother Adulph were educated by Saint Fursey in Cnobersburg monastery, located at Burgh Castle near Great Yarmouth. When Mercian forces invaded the region, the boys were sent to Europe and became Benedictines. Botulph was sent back to England in 647 to establish the Benedictine Order, while Adulph remained in Europe and became a bishop.

On his return, Botulph approached the little known King of the southern Angles, Ethelmund, whose sisters he had known in Germany. The King offered Botulph part of the royal estate upon which to build a monastery. Instead he settled for a desolate, barren site, reported to be haunted by demons.

With the support of Saint Syre, Saint Aubierge, and their brother, King Anna of East Anglia, Botulph founded the monastery of Ikanhoe (Ox-island), which according to the Saxon Chronicle, was established in 654 AD as a Benedictine abbey.

The site was surrounded by water and endless work was needed to make this austere place viable. But Botulph attracted enough brother monks and hermits and soon, through their hard work and faith, the monastery grew. The monks built several structures, turned large areas of marsh and scrub into productive grazing and farm land, and dispelled the local people's fear of demons.

No one knows for sure where Ikanhoe was - the two modern contenders are Iken in Suffolk and Boston in Lincolnshire. For many years local historians believed that the developing area around the monastery came to be called Botulph's Town, then Botulphston, with the name finally contracted to Boston.

However, more recent research suggests that the actual spot may be the village of Iken, near Snape in east Suffolk which, centuries ago, was almost encircled by the River Alde. The church there is also dedicated to St. Botulph.

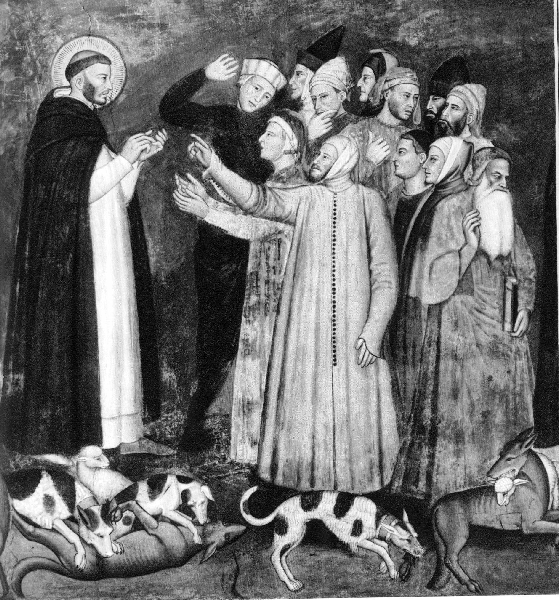

During his time at the monastary, Botulph also worked as a travelling missionary through rough, bandit-plagued areas of East Anglia, Kent and Sussex.

It is believed he died after a long illness while being carried to chapel for a compline service on 17 June 680 – the date his feast is commemorated. He was buried there at Ikanhoe.

A couple of centuries later his relics were removed to prevent them from being destroyed by invading Danes. It is believed they were transferred to Grundisburgh, a village near Woodbridge and later for safety distributed to the monasteries at Ely, Thorney and Bury St. Edmunds. According to legend, the relics destined for Bury were taken by night and the travellers were guided by a light that shone above the site of the new shrine. In the 11th century, a portion of Botulph’s relics were also taken to the Abbey of Westminster after it was rebuilt by Edward the Confessor.

Although there is some uncertainty as to where Botulph’s relics lie, what is not in doubt is that he was honoured by many churches dedicated to his name - well over fifty, chiefly in East Anglia. They bear witness to his untiring work which strengthened the Benedictine movement for many centuries after his lifetime.

Some of these churches were built at the ancient city gates to serve as safe-havens for travellers in times when robbers and footpads lurked along the roadways. Botolph is regarded as the patron saint for travellers and itinerants, and also farmers and agricultural workers.

His name is perpetuated not only at Boston in Lincolnshire but also by the New World city of Boston in Massachusetts. He gave his name to several English villages including Bottlebridge near Peterborough. Originally called Botulph’s Bridge, the village lost its identity when it became part of Orton Longueville parish in 1762.

Saint Botulph of Ikanhoe

Also known as

- Botolph

- Botulf

- Botwulf

- 17 June

- 25 June (Scotland)

- 1 December (translation of relics)

Profile

Born to a ChristianSaxon noble family. Brother of SaintAdolph of Utrecht. Educatedwith his brother at the monasteryof Cnobersburg (Burgh Castle), Suffolk under the direction of its founder, SaintFursey. When Mercian forces under KingPenda invaded the region, the boyswere sent to study at the monasteryat Bosanham, Sussex. He became a Benedictinemonkat Farmoutiere-en-Brie, Gaul(modern northeastern France), and was sent back to the British Isles in 647to establish the Benedictine Order there.

With the support of SaintSyre, SaintAubierge, and their brother, KingAnna of East Anglia, Botulph founded the monasteryof Ikanhoe in East Anglia, declining the offer of a part of the royal estate, and settling for a wild, barren site that was removed from people, reported to be haunted by demons, and which would require endless work to sustain the monks. For many years it was believed that the area that grew up around it came to be called Botulph’s Town, contracted to Botulphston, and later contracted to Boston in Lincolnshire, but recent reasearch has shown that the original site is another location. The Saxon Chronicleindicates that by 654Botulph had attracted enough brother monksand hermitsthat work begain on the monastery. Through hard work and faith, the monasterygrew in population; the monksbuilt several structures, turned large areas of marsh and scrub into productive farming and grazing lands, and dispelled the people’s fears of demons.

Botulph served as spiritual director for SaintCeolfrith, and worked as a travellingmissionarythrough rough, bandit-plagued areas of East Anglia, Kent and Sussex. His legacy continued for centuries in the strength of the Benedictinemovement in the Isles, and in the dozens of churches named for him, many of them built at city gates to serve as safe-haven for travellersin times when robbers roamed the roads, and many in port or river towns.

Born

- c.610 in East Anglia (part of modern England)

- 17 June680 of natural causes following a lengthy illness

- he died while being carried to chapel for compline services

- buried at Ikanhoe

- relics moved in 870 to keep them from being destroyed by invading Danes

- relics transferred to Grundisburgh in 983

- relics later distributed to monasteries at Thornery, Westminster, and Edmundsburg, Suffolk

- tradition says that for safety the cask of relics destined for Edmundsburg were taken there in the middle of the night, but the travellers were guided by a light that hovered above the relics‘ new shrine

- processions of the relics through Edmundsburgh has ended droughts there

- agricultural workers

- Bossal, Yorkshire, England

- Boston, Lincolnshire, England

- Boston, Massachusetts, USA

- Botesdale, Suffolk, England

- Botolph Bridge, Huntingdonshire, England

- Botolph’s Bridge, Kent, England

- Botolphs, Sussex, England

- farm workers

- sailors

- travellers

- abbot holding a church in his hand

- abbot holding a monastery in his hand

- blue field with undulating silver lines superimposed with an inverted gold chevron with a gold cross at its point (his coat of arms)

St Botolph was an English abbot who died in around the year 680. His feast day is on 17 June. Little is known of the saint, other than, as recorded in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle under 654, ‘Botulf ongan thoet mynster timbrian oet Yceanho’, ‘Botolph founded an abbey at Icanhoe’, meaning Ox-island. Some claim the abbey was at Iken in Essex, others in Lincolnshire, where Boston is a contraction of ‘Botolph’s town’.

As the patron saint of travellers, four churches at the gates of the city took his name, our neighbour St Botolph without Bishopsgate, St Botolph without Aldersgate at the other end of the City and St Botolph without Billingsgate, which was destroyed in the Great Fire of London in 1666. On their way to and from the City people would stop and pray and give thanks for travelling mercies.

O God, by whose grace the blessed Abbot Botolph,

enkindled with the fire of your love,

became a burning and a shining light in your church;

grant that we may be inflamed

with the same spirit of discipline and love,

and ever walk before you as children of the light,

through Jesus Christ our Lord.

Amen.

Voir aussi : http://www.pravoslavie.ru/english/print71898.htm

_-_WGA00312.jpg)